As a management consultant, I was once asked to help a CEO understand why the company safety record was tanking. I’m not a safety professional, although in my career as an HR leader, health and safety usually was part of my portfolio. The CEO was more interested in my strategic expertise than my safety expertise.

It didn’t take long to figure out a key problem. Leaders thought everything was great yet talking with them soon revealed the dreaded competing values syndrome. If value compete, or clash if you prefer, both values suffer. In this case two values clashed.

The first was around safety, its prime importance, its impact on people, and its impact on the bottom line. There were good, strong policies, procedures, and processes in place. Safety awareness was well supported. People attended safety meetings, there was good involvement in reporting and addressing hazards. People followed safe practices. But…

The second value got in the way. That was fast turn around time. The more quickly products were created and out to the customers, the happier customers were, the mor profit made, and the greater bonuses to the employees. The company was struggling (and eventually went under). This value wasn’t an espoused value, like safety, and that’s important.

Espoused values are what go up on websites and walls. They are the official values. Enacted values, though, are what actually happens and get lived in the workplace. They are often unspoken values, embedded in what people, especially leaders, say and do. In my experience, enacted values are far more powerful than espoused one, with enacted overriding espoused. Of course, the ideal is for the two to mesh – what is espoused is what is enacted, and the enacted values are in sync with each other.

Which brings me to my second point. Like any values, safety values must be enacted, and to enact safety values, they must be embedded into organizational design.

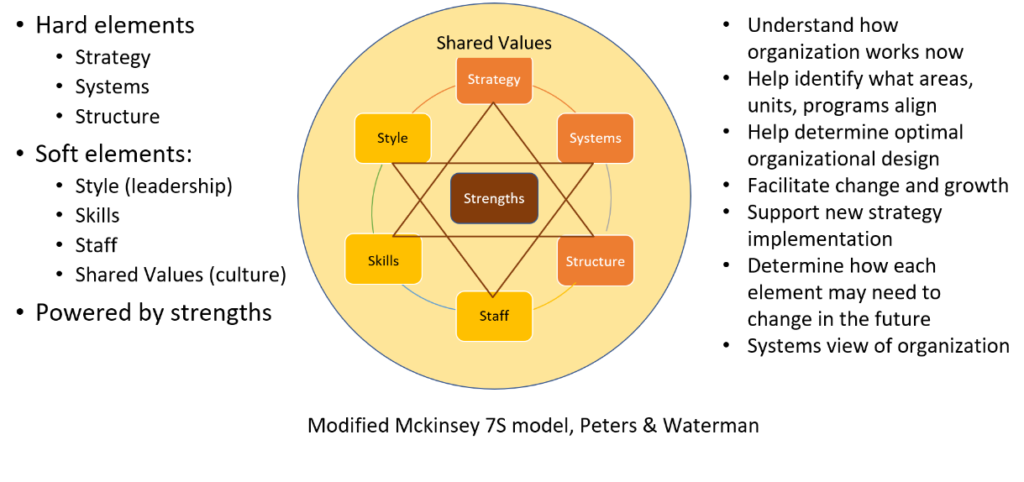

What is organizational design? Many people think of it as the organizational chart – how the organization is physically structured. Yet that is only one element of design. A model I use a great deal is the McKinsey 7S model. I like it because it is systems based and organizations are, by definition, open systems, influenced by external factors such as market trends, regulatory requirements, economic factors, and societal expectations, as examples that all influence how an organization operates. Further, organization are complex adaptive systems, constantly dynamic, with innumerable internal factors in play and those factors are constantly changing in and of themselves and in how they interact with each other. The system is NEVER static (or the organization dies). Thus, organizations are inherently unpredictable and mostly uncontrollable, much to the chagrin of leaders who like to think they are in control.

Although leading a complex adaptive system, many leaders still rely on reductionist thinking, aka cause and effect thinking. We see this often in terms of safety. An incident happens, find the cause, fix the cause, problem solved. Except it isn’t solved, because of the multiple factors and dynamic nature of a complex adaptive system. The combination of factors and their interactions has changed before anyone can start thinking about the cause of the incident and the solution isn’t 100% perfect.

So, what does all this have to do with organizational design and the 7S model? There are myriad factors at play in any organization and leaders cannot ever identify them all, let alone predict or control factor behaviours. Leaders need a framework that is manageable, such as 7S, for a variety of reasons, too many to get into here. The point is, using s model such as 7S enable leaders to look at the organization holistically and purposefully design the organization, how it operates, and how the pieces fit together to achieve desired results. If safety is a desired result, then it, too, must be purposefully designed in. Here’s the model.

You will note there’s 8 Ss here – that’s because this my modified model that I call 7S+1 because I’ve included strengths as the engine of how an organization operates.

When you design an organization, you ensure that each element is integrated with, is, in balance with, and in sync with the others – the hard Ss with the soft and each element with all the other elements.

When it comes to safety, then, leaders need to actively embed safety into each element. How will organizational safety values play out in strategy, for example? A strategy that doesn’t incorporate safety makes a mockery of espoused safety values, of course. How can safety be embedded in structure (which is primarily about how decisions are made, communication flows, and work gets done. What safety systems are in place?

For soft elements, how should leaders foster health and safety, how will staff interact with and understand safety, and what safety skills need to be in place? How is safety embedded into the overall shared values – the culture – of the organization that shapes values, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviours of the people in the organization (and often outside).

Obviously, this is an enormous topic, probably 10 books worth! My goal in this article is to raise awareness of two vital aspects of organizational safety. One, the need to address competing values, and two, the need for systems thinking to actively, intentionally, and purposefully design the safest organization possible.

Too often, organizations aren’t actively designed, so all the elements, which are always there, just hang out together in an unco-ordinated way with minimal understanding of the organization as a system. Safety ends up in a box by itself and not recognized as operating within the system. And safety breaks down.

jKEOfHhTUAvW